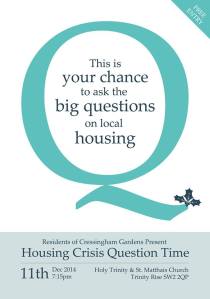

At the Lambeth Housing Crisis Question Time debate last month, organised by residents of Cressingham Gardens, an estate threatened by potential demolition, a tenant angrily questioned the six-strong panel of Councillors and academic experts “This is a community! Do you know about community? Do you live in a community?” Since recent research shows that around 1 in 10 people in Britain can’t name a single one of their neighbours, they perhaps did not. If decision-makers may have no first-hand experience of being part of a community, how can we expect them to value let alone protect this rare asset? We therefore might wonder, as another audience member rightly queried, is the impact of such ‘regeneration’ schemes on mental health and wellbeing being taken into consideration in decision-making? At present it seems not. Should it? Yes – here’s why, according to Lambeth’s own aims and ambitions.

At the Lambeth Housing Crisis Question Time debate last month, organised by residents of Cressingham Gardens, an estate threatened by potential demolition, a tenant angrily questioned the six-strong panel of Councillors and academic experts “This is a community! Do you know about community? Do you live in a community?” Since recent research shows that around 1 in 10 people in Britain can’t name a single one of their neighbours, they perhaps did not. If decision-makers may have no first-hand experience of being part of a community, how can we expect them to value let alone protect this rare asset? We therefore might wonder, as another audience member rightly queried, is the impact of such ‘regeneration’ schemes on mental health and wellbeing being taken into consideration in decision-making? At present it seems not. Should it? Yes – here’s why, according to Lambeth’s own aims and ambitions.

Lambeth Council are facing severe and compounding housing, mental health, and social isolation problems. On top of this, their budget has been slashed by 50% since 2011; no easy picture. The borough has one of the longest council housing waiting lists nationwide. 21,000 people are currently hoping to get a council owned property in the borough, a 210% increase since 1997. A further 1800 families are in temporary accommodation or homeless, while yet another 1300 are living in severely overcrowded conditions. If that wasn’t enough, half of the borough’s council stock is yet to meet the Decent Homes Standard.

Simultaneously, and very likely to be linked, according to the 2010 Marmot Review, the number of people using mental health services in Lambeth is three times the national average. In 2007, Lambeth was spending £276 per capita on mental health care, the fourth highest amount in England. In 2013, it was reported to have the highest number of benefits claims for mental health problems of any London borough.

A further interlinked factor is social isolation. As a nation, we are reputedly the loneliest in Europe. Particularly, a reported 25% of Londoners say they feel lonely all or some of the time. For adults using social care services, according to a Health and Social Care Information Centre report last year, this is especially the case. While the percentage of users who said they had ‘little social contact with people and feel socially isolated’ is 5.5% in England, that rises to 7.7% in London. In Lambeth, the figure is 9.8%, one of the worst in the country. In addition to the mental health crisis, our growing (and co-morbid) loneliness crisis is one that councils should be striving to avoid, not contribute to, at all costs – for cost it does, socially and financially.

Yet, following heavily criticised evictions from its so-called ‘shortlife’ housing co-ops, and a growing number of unpopular redevelopment plans on yet other estates such as the Guinness Trust and Myatt’s Field, as well as sheltered housing in Leigham Court, Lambeth’s current destructive approach to housing and thus its own fragile social fabric will arguably result in heavy long-term costs, both economic and social. Perhaps Lambeth Council do not realise just how compounded these issues are? However, if we are to take at face value the remit of one of its flagship initiatives, set up in 2010, the ‘Lambeth Living Well Collaborative’, then, actually, they do. So why the lack of joined-up thinking?

The ‘Lambeth Living Well Collaborative’:

The ‘Collaborative’ brings together commissioners, providers of health and social care services, service users and carers in order to implement the much-touted idea of ‘co-production’ to “radically improve the outcomes for people experiencing severe and on-going mental health problems”. It is intended to be a ‘demonstration site’ as part of Lambeth’s ‘Co-operative Council’ experiment; an experiment aimed at involving citizens more in designing and running services and lampooned as a gross paradox considering the borough’s dismantling of many housing co-operatives. Leaving the much-commented-on irony of the ‘co-operative council’ aside, a further contradiction lies in the Collaborative’s own vision: “that The Lambeth Living Well Area will provide the context within which every citizen…can flourish, contribute to society and lead the life they want to lead.” This is to be achieved by taking a holistic “Total Place” approach – “because the wider determinants of health have the most significant impact on health outcomes” – including housing and community.

The ‘Collaborative’ brings together commissioners, providers of health and social care services, service users and carers in order to implement the much-touted idea of ‘co-production’ to “radically improve the outcomes for people experiencing severe and on-going mental health problems”. It is intended to be a ‘demonstration site’ as part of Lambeth’s ‘Co-operative Council’ experiment; an experiment aimed at involving citizens more in designing and running services and lampooned as a gross paradox considering the borough’s dismantling of many housing co-operatives. Leaving the much-commented-on irony of the ‘co-operative council’ aside, a further contradiction lies in the Collaborative’s own vision: “that The Lambeth Living Well Area will provide the context within which every citizen…can flourish, contribute to society and lead the life they want to lead.” This is to be achieved by taking a holistic “Total Place” approach – “because the wider determinants of health have the most significant impact on health outcomes” – including housing and community.

One of the most progressive aspects of the Collaborative, for whom I did some work during a short stint at the Innovation Unit back in 2012, is their recognition of the detrimental effects of social isolation, and therefore their emphasis on building people’s resilience and “community-based interdependence” as a preventative approach to tackling mental ill-health, moving away from medical models of treatment. Part of this involves pumping money and resources into creating “lasting and sustainable support” for those experiencing mental distress “in their own communities and networks”.

According to Collaborative figures, the Council’s spends £3.4 million annually on supporting ‘social inclusion’ in the Voluntary and Community Sector. A further £3.15 million is provided by NHS Lambeth’s Clinical Commissioning Group to support a range of third sector organisations, including many activities focused on developing people’s safety-nets through social links, such as via Certitude’s ‘Connected Communities’ initiative and peer support, as well as building their ability to live independently. In 2012 Lambeth spent an additional £100,000 setting up three pilot ‘Timebanks’ in the borough – part of a nationwide campaign to “inspire a new generation of volunteers” in a reciprocal, and transactual, exchange system where time is the unit of currency given and received; the idea being that volunteering and being part of a social network is positive for mental wellbeing. All similar to the sorts of well-meaning ‘palliatives’ that (as mentioned in my last blog) George Monbiot wrote are being thought up to banish our loneliness epidemic.

While I am not knocking these efforts on their own terms, it seems supremely negligent and self-destructive to be priming the pump on the one hand, attempting to re-connect broken community links through expensive, artificial, top-down incentives, while at the same time, being involved in ripping up and shredding well-functioning, sustainable, and organically developed communities that are in existence. Why are Lambeth currently in the process of destroying some of the very precious few genuine communities that do exist in its borders? In particular, why are a Labour council dismantling housing co-ops, which Tessa Jowell has said to be “Britian’s best kept secret”, stimulating “active community participation”?

Lambeth’s communities shattered:

As Jonathan Bartley, Green Party Parliamentary Candidate, pointed out at the Housing Crisis Question Time debate, rare communities that help and look after each other are under threat. Thanks to a campaign, one such community in Streatham, where elderly and terminally ill people cook for each other, and are involved in the day-to-day of each others’ lives, was recently saved. This was not the case for another man, already evicted from his ‘shortlife’ housing co-op on Somerleyton Rd to make way for re-developments, who spoke of the devastating effects on his life of having his community destroyed: “I ended up in SLAM (South London and Maudesley hospital) because my mental health deteriorated”. Yet it’s not just the effects on those displaced. The dismantling of such communities impacts on us all.

Rectory Gardens residents protest the sale of their homes. *Photo borrowed from Lambeth Save our Services: http://lambethsaveourservices.org/2012/10/31/rectory-gardens-protest-halts-auction-viewing/

Take the further example of Rectory Gardens ‘shortlife’ housing co-op in Clapham Old Town, about which I am currently involved in making a documentary film. Residents, who have made these council-owned properties their home since the 1970s, are being evicted so that Lambeth can sell off the street of 28 houses at auction to raise funds. As I have written about in another blog, it is solely down to self-directed, co-operative efforts to maintain and improve the once dilapidated houses, through sharing skills and investing their own time, money and labour into their renovation, that the houses could now be worth around £500,000 on the market. Yet, as an OHCR global report on forced evictions and human rights uncannily describes, these sorts of development processes almost always affect the poorest members of society, and tend to be justified on economic grounds or as a ‘public good’. All too familiarly, Lambeth have sought to do just that. Cllr. Matthew Bennett, Labour Cabinet Member for Housing in Lambeth, told our film crew that since they cannot afford to refurbish the houses, which he says are ‘unfit’ for habitation (despite people residing there for 40 years with the Council’s permission), the council’s only option is to sell them on the private market, putting the proceeds towards the building of “1000 new council homes”.

They have so far made £56 million on the sale of 120 other shortlife houses; money which, incidentally, has not been ring-fenced for direct spend on housing. But residents have never requested for the council to spend money refurbishing the properties they themselves have done up over the years. They have suggested they keep looking after them as part of a wider Super Co-op, becoming secure council tenants in the process. This solution, which would have preserved the community, has been rejected. Yet, according to Lambeth Collaborative’s own policy on building social resilience, Rectory Gardens housing co-op as it exists today is precisely the sort of ‘natural’ community that the Council should be rushing over to support, promote, and publicly champion.

The houses may not be tidy specimens of a pristine suburbia, epitomised by the modern, gated housing block next door; the paint is peeling; bricks are crumbling; nature is pushing through crevices. But it is precisely this organic, imperfect condition, which also characterises the self-help community, upsetting some neighbours for its untamed ‘messiness’, that makes Rectory Gardens of such immense value – and I don’t mean economic.

The real and costly tragedy lies in the destruction of that rare modern urban entity – an organically developed, self-supporting community of diverse people, including young and old, families and unique characters, looking out for and helping one another without top-down ‘incentives’. Neither friendship clubs nor so-called ‘community development’ are needed here. Some of the residents are elderly; others have physical and psychological disabilities. One co-op member explains to me that, as a result, some contribute more to the community than others, based on their ability – this is the nature of being in a ‘co-op’. It is not transactual, nor always equal – unlike the concept of Timebanking, marketed on the idea that you get as much as you give.

Let me be clear – it is by no means a utopia. There are internal politics and tensions, as within any of the most cohesive of families. Yet this is what makes it all the more genuine – not perfect, not pristine, but raw and uneven, not something that can be easily manufactured nor constructed. As one resident put it “it’s like a village in the city here. We aren’t all friends, but we all know each other, and have learnt to live together, and there’s always someone to help you.” Building new council homes is a fine thing to do. But at the expense of stable communities that constructively and independently absorb and support a range of vulnerable peoples? I don’t think we have the idea of ‘value’ right if so. Furthermore, the idea of other co-ops being formed to take its place elsewhere, as Cllr. Bennett has implied, reminds me of the notion of biodiversity offsetting – an ecosystem is inimitable in its complexity. Are we to understand this as a casualty of apparently fungible social capital?

A further danger lies in the effect of residualisation – as social housing stock declines, those who do end up being council tenants are those most in need. Fabians calls this ‘poverty tenure’. This in turn compounds ill-health, concentrating the likelihood of developing mental ill-health in ever ghetto-ised social housing, increasingly located in neighbourhoods characterised by greater poverty – Rectory Gardens is indeed one of the last remaining social housing stocks in Clapham Old Town, a neighbourhood now largely affordable only to the wealthiest individuals. Residents have been re-housed elsewhere. The co-op houses will become private property. This does little to contribute to genuinely diverse and mixed communities in a fast gentrifying borough, while increasing the chances of later mental health repercussions.

One house on Rectory Gardens has already been sold, apparently to a foreign investor who lives overseas and is renting it out to two young professionals on the private market. It is the only property to look ‘smartened-up’; freshly painted white, with a polished front door, and a Banham security alarm adorned on its front. I’ve been told that the new tenants do not stop to say hello to anyone on the street; nobody knows their names. In the other houses that are slowly being evicted one by one, property guardians from Camelot and VPS have moved in. They are friendly enough, but they will soon be in and out – a transient and shape-shifting community at best. Semi-aware of his own unfortunate, and technically blameless, role in turfing the community out, one says “this street will definitely just become another characterless, soulless street of posh, expensive houses, no doubt about it.” Welcome to the new Rectory Gardens, now next door to one of a growing number of Lambeth’s ‘gated communities’. Is this the future that Lambeth Council envision? Pursuing present policies, it sadly appears so.

The repercussions of losing that community forever are yet to be fully known, or accounted for. It reminds me of Labour Councillors Nigel Haselden, Christopher Wellbelove, and Helen O’Malley who, in their 2007 election leaflets, said “these communities provide a welcome permanence to the borough” and “it would be senseless as well as expensive to evict them”. Yet shortly after they were elected they reneged on these promises. The only one who remained supportive, O’Malley, was de-selected. I wonder who will be proved right in the long-term.

Yet, in an interview for the documentary, and once again at the housing debate, Cllr. Matthew Bennett, was extremely pejorative about the co-op, which he claims did not take the opportunity to formalise itself with the Council. In actual fact, the Council never gave them that option. This in itself is telling of an attitude that sees bottom-up, non-institutionalised initiatives as a potential threat to be eliminated. Over on Somerleyton Rd the Council are involved in “setting up” what Bennett calls a “genuine” co-op; presumably a Council-sanctioned and initiated one, and one which Carlton Mansions shortlife housing co-op had to make way for earlier this year… Hardly befitting the ‘co-operative council’s’ claim of wanting to “transfer power to its citizens”. MP Steve Reed, who initiated the co-operative council concept in Lambeth, writes “handing power to the people is not straightforward because it means taking power away from those who currently hold it; they will often resist this change both individually and organisationally. Councils are structured to provide top-down services, and these structures need to change if we want citizen-led services to thrive”. It seems the radical implications of their own policies have not yet filtered through into action. Transferring power means stepping back and making space for the unplanned and non-bureaucratised; of letting things sprout through and emerge in untidy ways, not ‘tidying up’ and out those who dare to think and do differently.

Lambeth Living Miserably?

Back at last month’s Lambeth Housing Crisis Question Time Debate, Dr. Paul Watt from Birkbeck University concluded that, in almost exact contradiction to the Collaborative’s stated aims, “many of these regeneration schemes are actually producing sickness” rather than delivering “decent conditions in which people can live healthy lives”. Perhaps this is because Lambeth fails to recognise the difference between a ‘house’, a roof over one’s head, and a ‘home’, a place full of a sense of belonging, meaning, identity and community. Pressured by their long council house waiting list combined with severe budget cuts, it is no wonder that the council are looking for quick-fix answers that fulfil the minimum need. But this is terribly short-sighted. Yes there is a housing crisis. But if Lambeth are to tackle the other most severe and critical issue it faces – that of rising mental health problems and associated costs – it must think about housing in terms of providing and supporting the concept of ‘homes’, not merely four walls and a ceiling. It must value community and wellbeing above short-term economic gain.

That we are unclear on the long-term repercussions of so-called ‘regeneration’ schemes is evident in the fact that, as panellist Michael Edwards from UCL pointed out, regrettably there are almost no long-term studies being done to follow through these processes and assess wellbeing impacts. One such rare example that I’ve sourced online – a 2011 briefing paper by the Glasgow-based 10-year research programme GoWell, investigating the impact of investment in housing, regeneration and urban renewal on health and wellbeing in the city – tellingly found that while “[t]argeted housing improvement has generally had a positive effect on mental health…the effects of area-led regeneration are either absent or shown to have negative consequences.” More research is required to corroborate and map this more widely. I would also add to the bigger question, that as these communities become rarer and rarer, what do we stand to lose as a broader society? Without these functioning, self-created examples, we are all the poorer in our collective social imagination and aspiration.

Neither the aims of the ‘cooperative council’ nor the ‘Lambeth Living Well Collaborative’ are being served by the current local government’s short-termist attitude to housing, epitomised by current struggles in the borough; an approach that means we all lose in the end.

Housing crisis, economic crisis, mental health crisis, loneliness crisis – how many crises does it take to change the ideological lightbulb?

*************

To read more about Rectory Gardens, take a look at another recent (and apologies also lengthy/detailed!) blog by me on the Spectacle website, here.

If you want to listen to the full audio recording of the Lambeth Housing Crisis Question Time debate organised by Cressingham Garden residents, click here.

To learn more about housing campaigns in Lambeth, visit the Lambeth Housing Activists website.

To learn more about housing campaigns in London, visit the Radical Housing Network website.

(Blog republished on Brixton Buzz: http://www.brixtonbuzz.com/2015/01/lambeth-living-well-or-making-ill-housing-in-crisis/)